In recent abstracts published at the SVP 2013 and 2014 meetings, Mateus and Tschopp (2013) and Tschopp et al. (2014) work to address the question of intraspecific variation in Camarasaurus. The abstract by Mateus and Tschopp (2013) deals with a newly discovered camarasaurid (SMA 0002) that is referred to Cathetosaurus lewisi based on shared characters with BYU 9047 (holotype of C. lewisi). On the other hand, Tschopp et al. (2013) conduct a specimen-level analysis of all Camarasaurus specimens including the type specimens of currently recognized species of the genus (C. grandis, C. lentus, and C. supremus). The phylogenetic results reported by Tschopp et al. (2014) seem to not only reaffirm the distinctness of Cathetosaurus from Camarasaurus, but also support the validity of the three historical species of the latter genus.

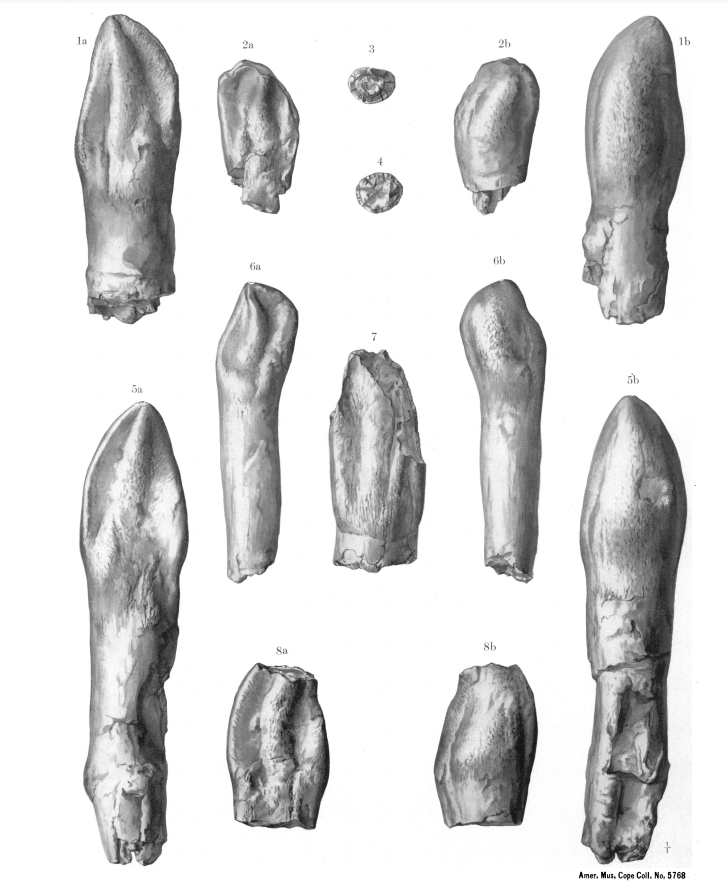

These preliminary results have prompted me to revisit the synonymy of Caulodon with Camarasaurus performed by Osborn and Mook (1921) and followed by subsequent authors. When placing the two nominal species of Caulodon (C. diversidens and C. leptoganus) in synonymy with Camarasaurus supremus, Osborn and Mook noted that AMNH 5768 and AMNH 5769 were similar to the maxillary teeth of a referred specimen of Camarasaurus supremus (AMNH 5761) in being robust and spatulate-shaped, but were hesitant to rule out the possibility of two different sauropods with spatulate teeth from the Morrison Formation. However, they did not compare the holotypes of Caulodon diversidens and C. leptoganus with the teeth of Giraffatitan or USNM 5730 (referred to Brachiosaurus sp. by Carpenter and Tidwell 1998).

|

Holotype teeth of Caulodon diversidens (AMNH 5768) (after Osborn and Mook 1921) |

References:

Carpenter, K., and Tidwell, V., 1998, Preliminary description of a Brachiosaurus skull from Felch Quarry 1, Garden Park, Colorado. In: Carpenter, K., Chure, D. J., and Kirkland, J. I. (eds.), The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 23 (2): 69-84.

Ikejiri, T., 2005, Distribution and biochronology of Camarasaurus (Dinosauria, sauropoda) from the Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Rocky Mountain Region. New Mexico Geological Society, 56th Field Conference Guidebook, Geology of the Chama Basin 2005: 367-379.

Marpmann, J., Carballido, J., Sander, P., Knötschke, N. 2014. Cranial anatomy of the Late Jurassic dward sauropod Europasaurus holgeri (Dinosauria, Camarasauromorpha): ontogenetic changes and size dimorphism. Journal of Systematic Paleontology. DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2013.875074

Mateus, O., & Tschopp E. (2013). Cathetosaurus as a valid sauropod genus and comparisons with Camarasaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts: 173.

Osborn, H. F., and Mook, C. C., 1921, Camarasaurus, Amphicoelias, and other Sauropods of Cope: Memoris of the American Museum of Natural History, new series, v. 3, part 3, p. 249-387.

Ouyang, H., and Ye, Y., 2002, The first mamenchisaurian skeleton with complete skull: Mamenchisaurus youngi: Sichuan Science and Technology Press: Chengdu. 111pp.

Rafael Royo-Torres & Paul Upchurch, 2012, The cranial anatomy of the sauropod Turiasaurus riodevensis and implications for its phylogenetic relationships. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 10(3): 553-583.

Russell, D. A., and Zheng, Z., 1994, A large mamenchisaurid from the Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, People’s Republic of China: In: Results from the Sino-Canadian Dinosaur Project. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 30: 2082-2095.

Sereno, P, C., Beck, A. L., Dutheil, D. B., Larson, H. C. E., Lyon, G. H., Moussa, B., Sadleir, R. W., Sidor, C. A., Varricchio, D. J., Wilson, G. P., and Wilson, J. A., 1999, Cretaceous Sauropods from the Sahara and the Uneven Rate of Skeletal Evolution Among Dinosaurs. Science 286: 1342-1347.

Steel, R., 1970, Saurischia: Handbuch der Palaoherpetology. Volume 14. Gustav Fischer Verlag.

Tschopp, E., Mateus O., Kosma R., Sander M., Joger U., & Wings O., 2014. A specimen-level cladistic analysis of Camarasaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) and a revision of camarasaurid taxonomy. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Program and Abstracts: 241-242.

Upchurch, P.M., Barrett, P.M., and Dodson, P. (2004). Sauropoda. pp. 259-322. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd edition). University of California Press: Berkeley.

Wilson, J. A., 2002, Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 136: 217-276.